Sandspurs and Sunburns

Grief on the North Carolina coast.

Growing up, each summer my family and I would spend about a week at my Nana and Pop Pop's house. Nestled in the small village of Avon on North Carolina's Outer Banks, the familiar rhythm of the bumps riding over Bonner Bridge's pavement told me we were nearly at Nana's.

I was the kid who pestered my family by asking incessantly how far we were, for the entirety of the five hour journey from Raleigh to Dare County.

My older siblings would sit in the middle of our silver Chrysler minivan, while my dad drove and my mom sipped her diet coke. I was put in the back with all of our luggage and my multitude of stuffed animals I meticulously chose for the trip.

My siblings, five and eight years older than I, would keep to themselves in the center seats. Like clockwork, Emily would plug in her iPod headphones and tune my voice out to the sound of Third Eye Blind and The Goo Goo Dolls.

Matthew, on the other hand, dealt with my incessant talking while he played on his Gameboy. It wouldn't be a complete road trip unless an argument over who got to play Pokemon Ruby ended in tears.

But time seemed to slowed down when we rolled into my grandparent’s driveway. My Nana would be waiting at the front of the house, poised behind the storm door. Pop Pop would always be fiddling with something in the garage as the van came to a halt.

Then came the mad dash to climb over my siblings and run up to my Nana. “Hey darlin’!” she would say in her unique Outer Banks accent, as she pulled me in for a hug. My Pop was always next in line as each of us piled out of the minivan.

My parents, understandably exhausted after driving five hours with three bickering kids, would usually head in and unpack the car.

As dinner approached in the evenings, I would run into the kitchen and see what Nana had cooking on the stove for dinner. I would stand on my tiptoes and see if she had out the pot. Her one silver pot - old and dented, but if I saw that pot out on the stove, I knew what was for dinner.

Stewed chicken and pie bread. Stewing anything and pie bread was acceptable for me as a child. Crabs, scallops, chicken, beef, fish, any protein that was on hand was used for dinner. My fondest memories with my Nana are in her kitchen.

Going in the sandy front yard to fetch some wild green onions for her recipes, putting my hands on hers as she slowly lowered the dough into the bubbling broth.

By the time supper was ready, my Pop was reclined in his chair in the corner, usually with his readers on and his curved nose tucked into the daily paper or an old copy of Reader’s Digest.

We would all crowd into the kitchen, connected into the dining room, and sit in our seats - my brother and perched at the kitchen counter - the designated area for youngins. We would tuck into our piebread, until our plates were clean. Lucky if we saved enough room for some of Nana’s homemade fudge, or three layered chocolate cakes.

After dinner, while the adults would sit on the front porch and chat, my brother and I would jump off the short porch and play amongst Nana’s roses, searching for critters. Our favorite was finding a type of insect that would create a hole and hide underneath it, then capture ants inside and eat them.

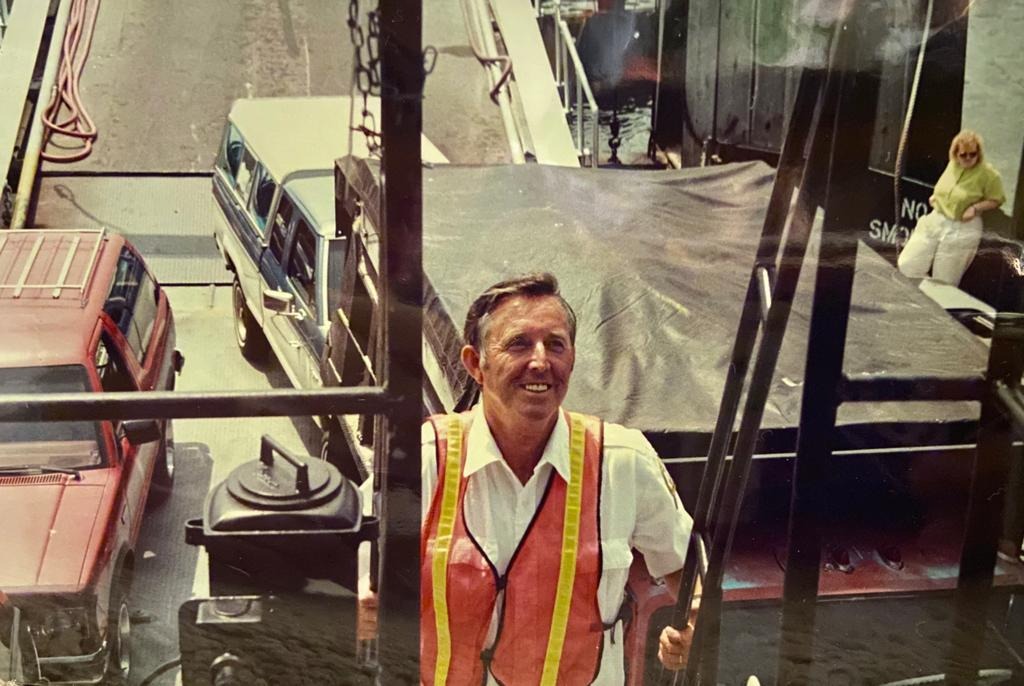

My Pop had a bright teal Chevy Silverado, fit with Hank Williams cassette tapes. To this day, I believe it’s the only music he’s ever bought.

The sticky heat of coastal North Carolina isn’t a feeling that’s easily forgotten. The stifling humidity made it feel like you were breathing in steam on most evenings, and the sun would turn into a haze.

My legs felt like they were glued to the car seat as we made our way towards my great grandfather’s house for the evening.

My only memories of him (he passed when I was eight) are of him sitting in his armchair in his home, and on the front porch at sunset. The village had a family of stray cats, which all seemed to herd around my granddaddy's home. I loved it.

Never mind that I’m severely allergic to cats - I would go and scoop up three or four kittens at once and try to show my Nana and Pop how cute they each were.

I would beg my mom and dad to let me take one home (they never did).

The best part of the evening was heading back to Nana’s after our long southern goodbyes.

I would take a bath, climb into my pajamas and tuck into the air mattress my mom had packed for me. I would sleep at the foot of the bed my parents slept in.

Just like clockwork, my Pop would come sauntering down the hallway in his boxers and undershirt (revealing the most intense farmer’s tan I’ve ever seen) and poke his head into my room. He’d make a silly face until I laughed, then sneak back out if my mom heard him talking to me after my bedtime.

I was about nine or so when things started changing in Avon noticeably. My siblings were too old to want to go swimming with me in the sound, to climb the cedars with me or go out back searching among the patches of briars and sand spurs to find wild onions.

My aunt, uncle, mom, dad, Nana and Pop would all entertain me while my siblings kept themselves busy.

Pop would take me on long drives through each of the villages on the island, pointing out where things used to be when he was a child and where parts of our family had lived over the years.

The most vital stop on our journeys was at a gas station on the outskirts of Avon, heading south towards Buxton. The little convenience shop was a wonderland.

I can still close my eyes and see the weathered cedar shingles and splintered stairs leading into the small shop, and still make a point to stop by each time I go to Avon now.

My Pop would slip me a crisp five dollar bill, and tell me to choose a soda and a candy bar to split. I would opt for a Milky Way, Reese's or Snickers, paired with a cream soda or root beer. Pop would eat anything that was sweet.

We munched on our treats as we drove through the small villages, passing the swimming hole affectionately nicknamed “The Canadian Hole”.

Pop maneuvered his truck into the parking lot and I would run into the water as he watched from the car. I would swim around until I was too tired or ready to leave.

I climbed back into the truck, the seats warm from the late afternoon sun. He would swear me to secrecy as we pulled back into the driveway after our little adventures, especially if we had eaten too close to dinner - Nana and my mom would scold us both if they knew we had ruined our dinner.

In 2011, Hurricane Irene wrecked the eastern seaboard. As my family fled the storm and came to stay with us inland, I was hiding by our back deck door as my aunts, uncles, parents, and grandparents had what sounded like an intervention.

My Pop, formerly one of the strongest men I knew, who would carry me over the patches of sandspurs to explore, was struggling to walk up the three stairs into their home after an onset of illness.

My Nana was getting worse too. Unbeknownst to his kids, Pop had fought fiercely to hide how bad her memory had gotten. But the gaps in her mind were becoming more and more apparent, resulting in the impromptu convention in the thick late August heat about what to do going forward.

I eavesdropped from inside our house as my aunts, uncles and parents sat surrounding them on the deck, trying to figure out what the way forward was as their house was destroyed in Hurricane Irene.

Things always felt different after that. I think it was the first time I truly grasped that my grandparents weren’t going to live forever.

230 miles away at home in Cary, I would see my mom’s parents often. My grandma is a force to be reckoned with - a headstrong, wicked smart woman with a sharp wit.

My grandpa was an incredibly kind man, and a bold proponent for nature and protection of North Carolina’s forests. A mycologist for his entire life, mushrooms were at the heart of what he loved. He was a fungi. (Get it?)

The first memory I have of grandpa was when I was in preschool, on “Dad’s Day”. The school would hold themed days for parents to come in, but on this occasion, my dad was traveling for work and couldn’t make it.

Grandpa cancelled his college lectures that day and came to my school, where we ate lunch together, made crafts and played outside. My grandpa had the best laugh, and gave the best back scratches known to man.

There’s a photo I like to look back on when I think about my time at my maternal grandparent’s house.

It’s of me, no older than four years old, wearing my Grandpa’s college hat and grinning ear to ear in front of his garden.

I helped Grandpa harvest what he’d grown that year, while Grandma watched with one of her thousands of sun visors on, accompanied with her Penn State Tervis.

Grandpa showed me it was okay to get messy. We would comb through the dirt in his backyard garden, harvesting the potatoes and asparagus he had grown that year. If we were lucky, he had a crop of corn.

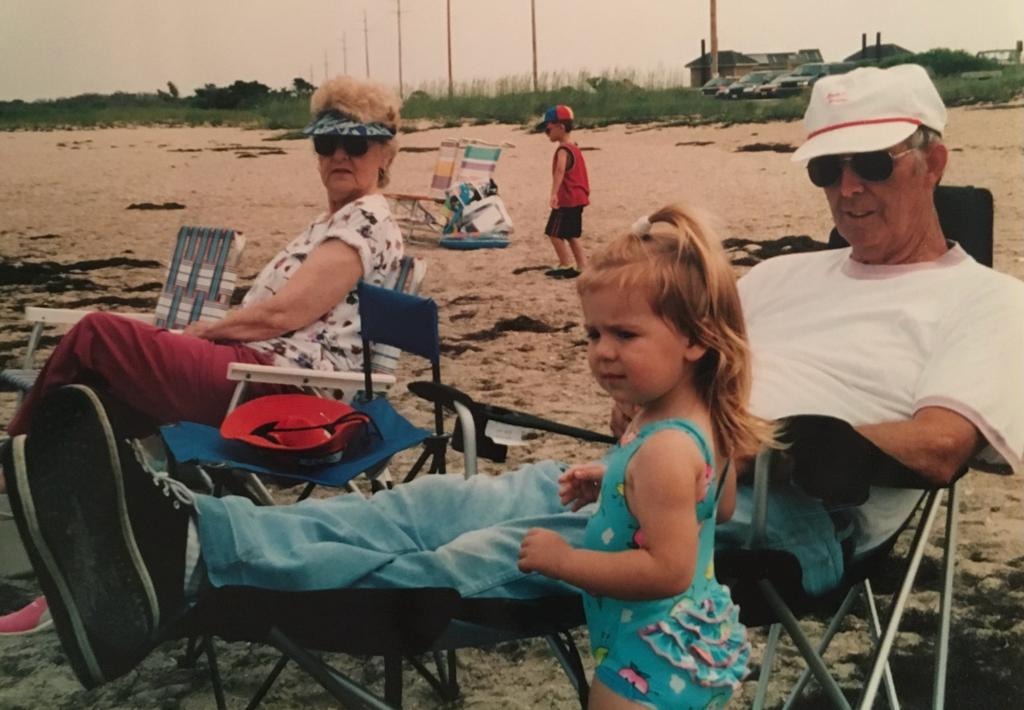

My memories with my grandma and grandpa are mainly centered on another small coastal North Carolina town, just outside of Wilmington. Each summer since I was born, the entire extended family on my mom’s side would come to a beach house there for a week.

Each summer, my siblings, cousin and I would swim and play on the beach to our heart’s desire, running into the beach house’s frigid air conditioned rooms just to grab a glass of Cherry 7-Up or a bowl of cheese balls to refuel.

The crème de la crème of the trip was ice cream night. My grandparents have an ancient Dolly Madison ice cream maker, which they hauled to the beach each summer.

I would sit with my elbows on the counter as my grandma and grandpa mixed the concoction and the mechanical whirring began.

The hour the mixture was spinning felt like a millennium as us grandkids would line up and wait patiently for our Styrofoam cup of homemade ice cream.

My mom and aunt lined up toppings ranging from whipped cream and chocolate syrup to heath toffee and gummy bears. The most divisive topping was the jar of red maraschino cherries - which caused an incident still referred to as “The Cherry”.

Someone slipped a cherry into my cousin’s ice cream (he despised them), but nobody fessed up to it. The culprit is still on the run to this day.

We sat with our legs stuck on a plastic beach chair out on the splintered deck, our salty hair blowing in the wind, eating the treat we’d waited hours for.

The experience was made complete each year after my grandma unveiled that year’s mystery themed, handmade t-shirt. She would spend all year cross-stitching each member of the family a shirt with a pattern based on something memorable from the former year’s trip.

Clues are sent weekly leading up to the beach trip, and each participant has to place a guess as to what the shirt color and pattern would be.

My Grandpa was a creative man. He loved to paint, create frames, and take photos. It was rare to see him without a camera, especially at the beach. One thing I miss most about him is our time creating together - painted wooden crafts, hot gluing glitter to a picture frame, anything involving art - he would do with me.

He was invested into his kids and grandkid’s lives. He took my brother and I into his campus laboratory one day, where he let us look at our hair under the microscope. Once while I was looking to earn a badge for Girl Scouts, he took me scavenging in a local forest on Thanksgiving morning looking for certain pinecones and leaves to press.

I’m a lucky girl to have had such loving, supportive grandfathers. Which made their deaths even harder.

Within a week in March 2013, life dealt my family a killer hand of cards. My Pop had been sick for a few years at this point, and we knew he was going to pass away soon. But on March 14, it was my Grandpa who died suddenly of a massive heart attack.

I was working on a diorama for school with my older cousin who was visiting when my mom got a phone call, and went out onto our back deck.

I think I knew what had happened after I heard her weeping, but it wasn’t until my dad pulled me into the foyer and told me Grandpa had died that I realized fully.

He died doing what he loved most - watching NC State play in March Madness. Grandma said he had eaten Bojangles while on the way to stay with her and our good family friend at the beach house that winter.

The chaos of the days following Grandpa’s death was made all the more painful when we learned Pop Pop had died on March 19.

My dad was sitting on the red brick front steps of my grandparents house in Raleigh when he got the phone call. His father had died, the very same day as the funeral for Grandpa.

Numbness.

I don’t think I really processed much after that. The days and weeks following were a massive blur, with a flood of condolences, flowers and cards filling our home.

For a 13 year old girl, I don’t think I really dealt with how I was actually feeling at the time. Having two major figures in your life die five days apart was traumatizing. I retreated a bit into my shell, albeit seeming to remain my outgoing self. But internally I was sort of frozen.

The years following Pop and Grandpa’s deaths were a blur. The traditions I had loved to share with my Pop and Grandpa had become painful reminders of what my family had been through in 2013.

Our visits to Avon used to be filled with things to look forward to: drives with Pop, Nana’s cooking, swimming in the sound and exploring near the creeks. But now they were a harsh memory of the people who were missing from them.

I was incredibly jealous and bitter that my siblings and older cousins got to spend so much time with both my grandfathers before they died. Sometimes I still am. It’s selfish to say that now, but at the time I was angry.

Watching Nana’s stories become more and more inconsistent as her memory loss progressed was soul shattering. For a 13 year old, it was inconceivable to imagine what she was going through after losing her husband of fifty years.

My Grandma grieved in her own way. I don’t know how she kept it together in front of us grandkids for so long. When she went back to Surf City the year after Grandpa died, I don’t know how she had the strength.

I dreaded having to go to the beach that year - the house which had so much joy before in the summers seemed like it would be empty without one of the most vital members of the family.

Yet, we went back. To Avon, to the beach, to the mountain creeks that Grandpa had fished so many times. Each year became a bit easier, but the grief comes in waves.

I don’t know what made me write this. It’s been ten years now - a decade since I’ve heard Grandpa’s snoring after a large Thanksgiving meal, or seen Pop tinkering in his garage as we pulled into the driveway.

The grief I’ve felt for ten years is similar to two things that hurt me when my Pop and Grandpa were alive - sunburns at the beach and the sand spurs stuck to my heel in Avon.

Those sandspur patches Pop used to carry me over in the backyard are still there. And they still sting like a bitch when they’re stuck into your heel.

I suppose that’s what grief for my Pop has felt like. A sudden sting, without warning, hits me sometimes when I eat a candy bar while driving down highway 12.

When I swim in the Pamlico Sound in the evening and don’t see his teal Silverado sitting in the parking lot, a fleeting pang of grief hits me that’s as gone as quickly as it came.

Grandpa's death was unexpected, and the grief crept over me more quickly than Pop’s - which I had more time to prepare for mentally.

You know that warm stinging sensation you get after you shower and realize you’re sunburnt? It’s a deep heat that comes upon you in a matter of hours.

It’s a sting that you feel when your skin brushes up against the fabric of your clothing. You can’t avoid it, you know it’s there, yet you forget until the friction of your clothes and skin reminds you of it.

When I see a mushroom growing in a weird place, or see a Hemingway novel in a bookshop, I think of him. I sometimes forget how painful it is that he’s not here until I see a reminder.

Both sunburns and sandspurs are painful in their own unique ways, but I’m grateful for the harsh sting.

It reminds me of the people I’ve lost, the pain I felt and the pain I still feel 10 years after March 2013.

I wish I could speak to my grandpa and Pop. Tell them everything I’m up to, ask their advice and opinions.

But there's a comfort knowing that my Pop is in each sunset I see at the harbor in Avon.

That Grandpa is saying hello each time I see a mushroom growing on a tree in the middle of London.

Ten years later, and I still miss them as much as I did in that chaotic March.

Post a comment