Atlantic blight – Opioid Addiction in the US and UK

As one walks from Liverpool’s Lime Street station into the busy city centre, countless Beatles memorabilia stores, high-end shopping centres and museums meet the eye. Seagulls squawk as they try to grab chips from the hands of passersby.

4000 miles away, the narrow barrier islands of America’s North Carolina coast are a stark contrast to the busy port city in Northern England. Yet, there’s an invisible thread between these two communities. Both are coastal capitals for drug abuse and socioeconomic issues in their countries.

For two regions separated by the Atlantic Ocean, the similarities are vast. Since 1999, deaths related to opiate abuse in both the US and the UK have increased steadily each year. In the US, the Centres for Disease Control (CDC) recorded 21.4 out of 100,000 people dying of opiate abuse in 2020. The UK witnessed a similar increase, reaching upwards of 3000 drug-related deaths in 2020, according to Statista.

The trend of coastal communities experiencing high levels of drug abuse has become a common phenomenon witnessed in both countries. The 2021 Adult Substance Misuse Treatment Statistics Report, released by the UK’s Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, revealed that the number of people seeking treatment for opiate and crack addiction decreased significantly between 2018 and 2021, despite experts estimating drug abuse in the UK to be at an all-time high.

Despite these funding increases, centres are still struggling to keep up with the demand of their services, and levels of addiction are still rising.

Similarly, the number of drug overdose deaths in North Carolina increased by 40% in 2020 as compared to 2019, despite government initiatives to decrease overdoses and deaths, according to the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. Despite these funding increases, centres are still struggling to keep up with the demand of their services, and levels of addiction are still rising.

The UK and coastal North Carolina share many common characteristics, despite being 4000 miles apart. The same areas in North Carolina experiencing these vast issues with drug abuse were actually settled in the early 1700s by people from cities including Liverpool, Plymouth, and Blackpool.

One would assume 300 years of separation would make these areas develop quite differently, but they are facing eerily similar issues. Healthcare, accessibility to drug treatment centres, housing and other factors are playing into the high levels of drug abuse in these coastal cities.

The current addiction epidemic facing both the US and UK appeared in three waves. The first appeared in the form of high levels of prescription opioids commonly prescribed in both countries after their creation in the 1990s.

After high levels of dependency were created by these prescriptions, a second wave appeared in the form of high use of heroin in both countries, but the US was hit hardest by this. The third wave, which both countries are currently dealing with, is the synthetic opioid phase: fentanyl being the main culprit.

Liverpool, England

A port city with an economy based on trade and tourism, Liverpool is a mirror image of Wilmington, North Carolina, with both its rich and complex trading history and deeply rooted issues with drug abuse. Like the US, the UK has continued to see an increase in drug abuse, with most of the hotspots being coastal towns and cities.

Liverpool, Blackpool, Hastings, and Brighton all rank within the top fifteen cities in the UK with the highest levels of drug abuse, with Blackpool ranking highest for the number of drug-related deaths.

The reasoning as to why these coastal cities harbour such high levels of addicts has been attributed to the housing situation, untreated illnesses, and various traumas of addicts. Robert Beattie is a former addict from Liverpool who now works as a counsellor in the Tom Harrison House, an outreach and treatment centre for former military personnel who are struggling with addiction. He said he still struggles to grasp the question of why coastal communities are so affected by addiction.

“It’s that million-dollar question. There are so many theories around. Whether it be low social background, low economic background, whether it be poor education, whether it be poverty, whether it be - I don't know- there are so many factors you can look at. I think it's hard to pinpoint,” Beattie said.

Reflecting on his own battle with addiction, Beattie said a lot of undiagnosed traumas were involved. His father had undiagnosed PTSD from the Second World War and turned to alcohol to cope.

His mother was chronically depressed but went untreated due to stigmas surrounding mental health and a lack of mental health services at the time. Beattie said he turned to drugs to cope with the pain he felt growing up.

“When I started using it, it made me feel good. It took away all that pain. Now, through working in the job role that I'm in, I work with clients who have had great childhoods, with no money issues. They’ve had their needs met, they felt loved, they felt cared for. They, you know, on the surface, the story, it's okay, but they still become an addict,” he said.

Despite the demand seen in cities such as Liverpool for affordable treatment, early intervention into high-risk families and individuals, hundreds of drug treatment centres have shut their doors due to a lack of funding and privatisation of treatment.

“It's completely underfunded. I know that a lot of the guys here must work hard to get funding in place to get the clients, and it can be heartbreaking and very difficult,” Beattie said. “If people are desperate, and they can't afford it, we'll have a bursary where we might pay half of it ourselves.’’

Dare County, North Carolina

The Outer Banks of North Carolina comprise Dare County, a coastal region which attracts millions of vacationers each year to its isolated beaches. The rural area has a population of only 36,000 permanent residents across its nearly 1500 square miles, but that number swells to nearly five times the amount during peak tourism periods.

In 2019, substance abuse was ranked as the most pressing issue in Dare County. The NCDHHS Drug Abuse Dashboard found that the rate of overdose deaths among residents of Dare County in 2021 was 32.4 per one thousand.

The prevalence of coastal areas such as Dare County to be hotspots for drug abuse isn’t surprising, said Miranda, a recovering addict from an Outer Banks village with only 900 year-round residents.

“Living in a small town, you have a small number of people. So, this small number of people sticks together. Because you live in this small coastal town, you know where to go. Right now, I know exactly where I could go and get anything I wanted, and they would sell to me without a doubt,” Miranda said.

Miranda fell into drug addiction after suffering injuries from a car wreck while working in 2011. Her injuries were so extensive that her doctor prescribed high levels of Roxicodone, an opiate drug.

Her girlfriend at the time began abusing these pain pills, but Miranda was able to get more and more prescriptions written from her family doctor due to the extent of her injuries.

“She was a family friend, and she was new here. She'd only been here maybe two years. I think she was a little naive about what was going on in the community. I played on that. I would cry, say I work all the time, I'm in pain, which was true. I did suffer in pain, but I embellished it to an extent that I would get the medicine,” Miranda said.

She continued to receive written prescriptions for opiate pain medication from June 2011 until April 2012- nearly an entire year. When Miranda attended an appointment in April 2012, the doctor said she was unable to keep writing prescriptions. At this point, she was addicted to opiates.

Her doctor suggested going to Virginia, about 100 miles north of her Hatteras Island village, for a pain management programme. Miranda obliged, but once she arrived at the pain management clinic, the doctors began prescribing her more opiate pain medication.

“The doctor who prescribed me OxyContin in pain management retired, so a new doctor then put me on this thing called Opana. To this day, I have never felt a feeling that good,” Miranda recalled.

The drug Opana has now been discontinued in the US. Throughout her ordeal, Amanda said doctors did not require regular MRI or CT scans to check on her injuries – they just kept prescribing more pain medication.

In 2015, Miranda's father intervened and told her doctor what was going on. The prescriptions stopped coming in, and she began looking for them illegally.

“You're searching from the moment your eyes open, you think to yourself, “Okay, how can I get more medicine? I have my medicine for now, but I need medicine later.” And you focus on it, constantly, day and night. You may have it, but you got to figure out when you run out how you're going to get it. It’s like a game of chase the dragon,” Miranda said.

In 2017, she went on medication to help wean her off of opiate dependency and was clean for a while. In 2018, however, she turned to heroin. Miranda said her pain was so great from detox that she attempted to get into the pain management clinic, but wait times were up to three months long.

At the end of 2018, she was arrested and got clean, and has been ever since. But her small town on Hatteras Island continues to suffer from rampant drug addiction. Miranda attributes a lot of the trends of drug abuse in her community to money struggles, but cites trauma as the main characteristic in addicts.

“Living here is, for a lot of people, it's hard. If you look at the people around here, like when I got bad off, my grandmom had just died. Then a year later, my grandfather died, plus-” she began to tear up during our interview.

“I feel like I never got help. With my uncle, whom I looked up to. He died from drug issues. People who have addictive personalities might not even know until they experience trauma. Once they take the drug, they're like, oh, this numbs me,’’ Miranda said.

Many residents of Dare County are unable to afford treatment at rehabilitation centres, she said. Despite funding initiatives from state government and recent arrests of high-profile dealers in Dare County, Miranda said the problem is still ravaging through her community. Wait times at the clinic in Virginia have since improved, she said, but issues persist in accessibility in Dare County for help.

Blackpool, England

It is not simply proximity to major highways and high levels of drug trafficking that contribute to these coastal communities’ high levels of drug abuse. In Blackpool, the housing market is a big contributor to cheap accommodation for addicts who may come to the city for a fix and decide to stay.

After the Second World War, Blackpool continued to see a boom in its economy as a domestic vacation destination. Emily Jane Davis works as a harm reduction lead within the public health team at Blackpool Council and said this former economy of tourism resulted in many bed and breakfast-type accommodations being built to meet the demand of vacationers.

“In the 1970s, when people started to go abroad for their holidays, Blackpool started to see a decline. Now, a lot of the old bed and breakfast accommodations are rented out very, very cheaply,” Davis said.

Referred to as HMOs (High Multiple Occupancy Properties), the former vacation accommodations are left unmanaged and rented out to a transient population for a low price. During Blackpool’s busy tourism season, Davis said many people come into the town due to this cheap accommodation, but bring their problems, such as addiction, with them.

Lack of economic opportunity has been a major issue in the Blackpool area. Davis said the area is experiencing economic deprivation like never before.

“Blackpool wasn't a fishing town, but a place called Fleetwood, further north, has seen a massive decline. I’m actually from there. There's hardly anything there now, probably since the sort of late 70s and 80s. They still have the fishing community, but it's very, very small,” Davis remarked.

Dare County, in the US, has been experiencing similar issues. In our interview, Amanda remarked on how the local harbour in Avon was filled with working fishing boats in the 1980s and 1990s.

Environmental restrictions and related fish quotas entered the picture in the same time period, resulting in the majority of local fishermen retiring and turning to more reliable jobs.

In his book The Drop, author and former addict Thad Ziolkowski delves into the reasoning behind why many coastal regions are hotspots for drug abuse and connects the issue to his experience growing up surfing.

Identity crises, many of which turn individuals to addiction, have become common in coastal communities, partially due to this upheaval of traditional work.

“That’s why people have such an intense issue with addiction – because people there are cut off from traditional forms of identity.

"In the case of someone whose father passed along a business that no longer exists, like a fish shack, then you’re suddenly in a position of saying, “Well, what now? Who am I, what am I,” he reflects.

Devon, England

Growing up near the Devon coast, surfer Andrew Cotton was never out of the water long, and when he was on land, he was constantly thinking about getting back into the water. Devon is a county in southeast England, bordering much of the coast.

Since 2021, drug-related deaths in Devon have been at an all-time high since records began, according to the Office for National Statistics. Hospital admissions in the county for drug misuse have also been increasing for the last few years.

Growing up in North Devon, Cotton said he didn’t witness opioids or heroin. The culture with Devon surfers was more focused on alcohol and smoking marijuana, which he said is a hard thing to balance. He’s witnessed people go down the wrong path of partying but didn’t recall any intense issues he saw in his community with addiction.

For Cotton, surfing has always been a positive sport which has given him direction. The ocean gives him a focus and a goal to his day.

“I think a lot of times when people wake up, and have no plans, the ocean or that activity is free for use. Having that focus, I think, is really important. It really helps with mental health, addiction or whatever you're dealing with,” he said.

Cotton began surfing in the 1990s on the North Devon coast. He said he quickly became obsessed and kept searching for larger and larger waves. In 2010, American surf legend Garrett McNamara invited him to Nazaré, Portugal, to surf some of the largest waves recorded in the world.

For years, Cotton surfed these massive waves on Portugal’s coast, with many waves recorded upwards of 100 feet. In 2017, however, he suffered a major wipe-out that nearly ended his career. Cotton broke his back while surfing Nazaré.

“I was very fortunate because I had my injury managed by my sponsors. Some good people were around there and helped guide me through,” he said of the injury.

Cotton was lucky. A large percentage of those who fall into drug abuse do so after an injury, where they may be prescribed high-dose painkillers. Cotton recovered and is surfing again, but he said surfing and extreme sports can be lonely. After surfing such massive waves, he said the lows can be worse, which he thinks could bring on drug addiction without the proper help.

Thad Ziolkowski agrees. In his book The Drop, Ziolkowski connects the surfing world with the culture of addiction.

Growing up surfing in the 1960s and 1970s, Ziolkowski has witnessed the evolution of the surfing movement, from long boards to short boards, big wave surfing and other innovations.

Using Nazaré as an example, Ziolkowski said the sport is reaching the very limit of what the human body can withstand, much like a high-level drug.

“Someone who injures themselves, say, after surfing Nazaré, is primed to become an opioid addict.

"Big wave surfers share an essence with addicts: to overcome the effects of tolerance, having grown familiar with a certain rush, craving something more powerful, something like their first or best wave, that haunting gold standard, they increase the dose to the very limit of what their bodies can survive,” Ziolkowski said.

Many of the big wave riders Ziolkowski spoke to say the aftermath of the big wave session is the most difficult to navigate psychologically. The surfer wants more after this peak experience. Coupled with an injury, the come down from such a surfing ‘high’ is heightened.

“People with addictive proclivities seem drawn to surfing for its physical and psychic demands, intensity of its pleasures, trance-like state that steals over one in the surf zone,” he recalled.

Brighton, England

215 miles southeast of Liverpool lies Brighton, a beach city only an hour’s train ride from London. Like Liverpool, Brighton has a high level of drug abuse, ranking number one in the UK for abuse of cocaine, ketamine and MDMA.

One in five Brighton residents has used cocaine within the past year, according to data gathered by rehabilitation clinic Delamere, based in Norwich. Michaela Sheppard is a therapist and member of the British Association for Counselling & Psychotherapy.

She currently works with addicts in Eastbourne, Hastings, London, and Brighton as a part of Project ADDER (Addiction, Diversion, Disruption, Enforcement and Recovery), a programme created by the Home Office and Department for Health and Social Care. Project ADDER was created in 2019 to deliver funding and assistance to cities affected by high levels of addiction and drug misuse.

Sheppard believes one of the leading factors contributing to addiction is a lack of early intervention. Children who live in chaotic households, have misdiagnosed mental illnesses and live in economically deprived areas are primed for addiction, she said.

“All the clients I work with have all been children who slipped through the net. In these chaotic households, there's an awful lot of sexual abuse, physical, and emotional neglect. I really do think that people, teachers, and schools need to be a lot more aware of these children that are coming in,’’ Sheppard said.

Many of these children, Sheppard cites as slipping through the net and turn to drugs to have a sense of identity, to feel acceptance and to get friendship, which they may not receive at home. Helping current addicts is important, she emphasised, but the cycle of falling into addiction will continue forever unless parents and teachers don’t intervene when they see the signs of early addiction.

Sheppard works as the lead therapist for the Hastings and Brighton area, which she said is doing incredibly well with funding due to Project Adder. She does, however, notice a strong correlation with high levels of drug abuse in coastal towns.

Like Liverpool, Brighton, and Hastings also have unmanaged former vacation properties which are rented out cheaply, something which is appealing for an addict looking for an area with easy drug access and cheap rent. Speaking on the high levels of drug abuse, Sheppard said she’s never seen anything like it before.

“Down the street, you see open dealing, you see smoke, constant weed smoking, which I know is on the softer end of the scale. But it is absolutely rife. Every family could be touched by some form of drug dependency,’’ she said. “There’s a lot of new drugs coming on the market. People who have got a real drug dependency, if it's going to be opiate addiction, they tend to stay on the opiates. I think there's an awful lot of new drugs coming in, Brighton, for example,” Sheppard said.

Wilmington, North Carolina

Just south of the Outer Banks lies Wilmington, North Carolina: a crossroads of two major interstate highways. Interstate 40, which runs from North Carolina to California, and Interstate 95, which runs from New York to Florida. Wilmington, a port city in southern North Carolina, has been ranked as the number one city in the state for drug abuse for the past decade.

Coastal Horizons, an addiction treatment centre in Wilmington, provides outreach and treatment services to Wilmington and its surrounding counties. Jane McDonald has worked as a coordinator within the centre for more than twenty years, and said the community has a real issue with access to drugs, and not just illegal ones.

Prescription drug misuse is one of the leading reasons behind turning to heroin. Within the centre’s listening groups with current addicts, McDonald said a lot of the adults in the group weren’t aware of prescription drug misuse, and didn’t view it as ‘drug misuse’, since it’s prescribed by a doctor.

“Prescription drugs, or alcohol, they're very easy access at home, either people’s own homes or someone else's home, as well as people sharing, whether that's unintentionally or looking for a mood-altering experience,” McDonald said.

Jen Horne is a peer support specialist at Coastal Horizons. A former addict herself, she said the best way she thought she could be of service after recovering was to work with people who are struggling with addiction. As part of the quick response team at Coastal Horizons, she responds to individuals who are at risk of overdosing or have recently overdosed.

“We help with getting them to the proper care, whether it be treatment, recovery, hospitalisation, or whatever it is that we feel like they need at the time,” Horne said.

The current initiatives to lower the number of drug-related deaths and abuse across North Carolina is part the North Carolina Opioid and Substance Use Action Plan (NCOSUAP).

This plan allocates funding to community-based organisations, such as Coastal Horizons, to extend treatment services, outreach, and overdose prevention. Even with this initiative, Horne believes it is not enough for addicts, who are already struggling financially on top of their addiction.

“Nine times out of ten, they're already broke and beaten, and they're already out of resources. They’re not working, they've lost the ability to be a productive member of society, and when you're asking them to get treatment, or go into a recovery house, yet there's no funding to help them with it, what are we really doing? We’re sending them back to the streets,” Horne said.

A lack of understanding of addiction by local and state governments feeds into this disparity in treatment, according to Horne. Wilmington is currently seeing a large increase in the use of crystal meth and fentanyl contaminated drugs.

Horne said she has never seen anything like it before, but attributes it to the accessibility of drugs in the community and the fast-paced lifestyle of a tourism-based city such as Wilmington.

Deanna Stoker is a crisis centre counsellor at Coastal Horizons and agrees with Horne’s theory on easy accessibility to drugs due to the major interstates which connect near Wilmington.

Stoker said many patients at Coastal Horizons have mentioned the high numbers of drugs trafficked into Wilmington on these interstates, but Stoker believes the city’s ports also feed into the level of drugs entering the area.

“Cocaine is making a big comeback. This is something I've seen… use of stimulants always rises after a period of high abuse of depressants. We also have a lot of fentanyl contamination,” Stoker said of the current drugs being used by patients at Coastal Horizons.

William is a North Carolina native who fell into drug addiction in his adolescence. He began smoking cigarettes and marijuana at a young age, then turned to alcohol when it was available. As he entered his teenage years, he said his usage progressed in both quantity and frequency. He then turned to heavier drugs, mainly opiates, at the age of seventeen.

William has been clean from all mind and mood-altering drugs since January 23, 2013, and now counsels fellow addicts in recovery. He said he knows of many people who recovered from their addiction without attending inpatient or outpatient facilities in North Carolina, but many people he knows have gone through programmes available in coastal North Carolina.

“Treatment can be very expensive, and many facilities require insurance to attend, so socio-economic factors can be a hurdle for those seeking treatment. There are programs available in eastern North Carolina that are less expensive (or state-run), but the quality of care seems to be lower than other facilities and programs,” William explained.

There does seem to be a genetic or hereditary link which predisposes certain people to addiction, he believes. The children of addicts do have a higher chance of becoming addicts themselves. Like Amanda, William also believes emotional traumas are strongly correlated with drug abuse.

Though accessibility to quality treatment in eastern North Carolina remains an issue, William said, there has been a shift in public understanding of addiction, as it has touched nearly every family in the US.

“Addicts are not bad people, but sick people. Everyone knows someone who has suffered. Letting people know that they are not alone and can recover if they have the capacity to accept help, I think, is what works,” William explained.

With initiatives such as the NCOSUAP implemented by the NC state government to lessen drug deaths and overdose numbers, the number of drug-related deaths were expected to decrease.

However, the latest numbers released in 2021 reveal they seem to have only risen due to a lack of access to treatment facilities and high levels of drug trafficking in the coastal North Carolina area.

Moving forward

Treatment and outreach centres such as Coastal Horizons are implementing more comprehensive drug outreach programmes to combat the root causes of drug addiction in the community. Stoker said the centre is in the process of surveying her surrounding community to see what people’s coping strategies are.

“One of the things that we're focused on in our community is building resiliency skills and using the Community Resiliency Model (CRM) to build people skills to help them. It's teaching people about their parasympathetic and sympathetic systems and how to activate them or deactivate them,” Stoker explained.

She compared the parasympathetic and sympathetic systems to ‘getting out of one’s zone’. This new initiative by Coastal Horizons is to assist addicts to address how they’re feeling before they use – to see if they can ‘switch off’ the urge with more education and resources available to them.

Providing education on coping skills, Stoker said, such as walking, meditating, talking to a friend, journaling and more, can help distract addicts from turning to the drug when something goes awry in their life.

Misconceptions of addiction continue to feed into the lack of public knowledge surrounding the disease. Horne said the biggest misconception anyone could have about addicts is that they can simply stop.

“They think it's not a disease, and for me, that was not true. I have three kids that I love, but even my love for them just wasn't enough. It came down to using against my will, using when I didn't want to. I told my son a few weeks ago, “Don't think for one minute if I could have stopped, I wouldn't have.”

"It didn't mean that I didn't love him, it just meant that the addiction I was in had a greater hold on me,” Horne said on her battle with addiction. “It'd be nice to be able to say, 'Okay, I don't want to use again,' and that would be it, but for people to say all, it's all in your head - people just don't get that there's more to the addiction,”

Though programmes such as Project ADDER in the UK and NCOSUAP in North Carolina have created plans to address this issue of drug addiction, access to treatment facilities and resources for existing facilities continue to be major issues within these coastal communities.

As of today, both William and Miranda are clean from drug misuse.

“I got kind of lost for a little while there. And now that I'm running a successful business. You need a doctor and a therapist. They're the ones that helped me, because they helped me wind down, talk, and understand my triggers, they helped me understand how you go back into life again,” Miranda said.

“Addiction is not a matter of moral failing or lack of will power. It is the insatiable need of a person who has lost the power to choose whether or not they will use. It leads people to say and do and believe things that they would not do under normal circumstances,” William said.

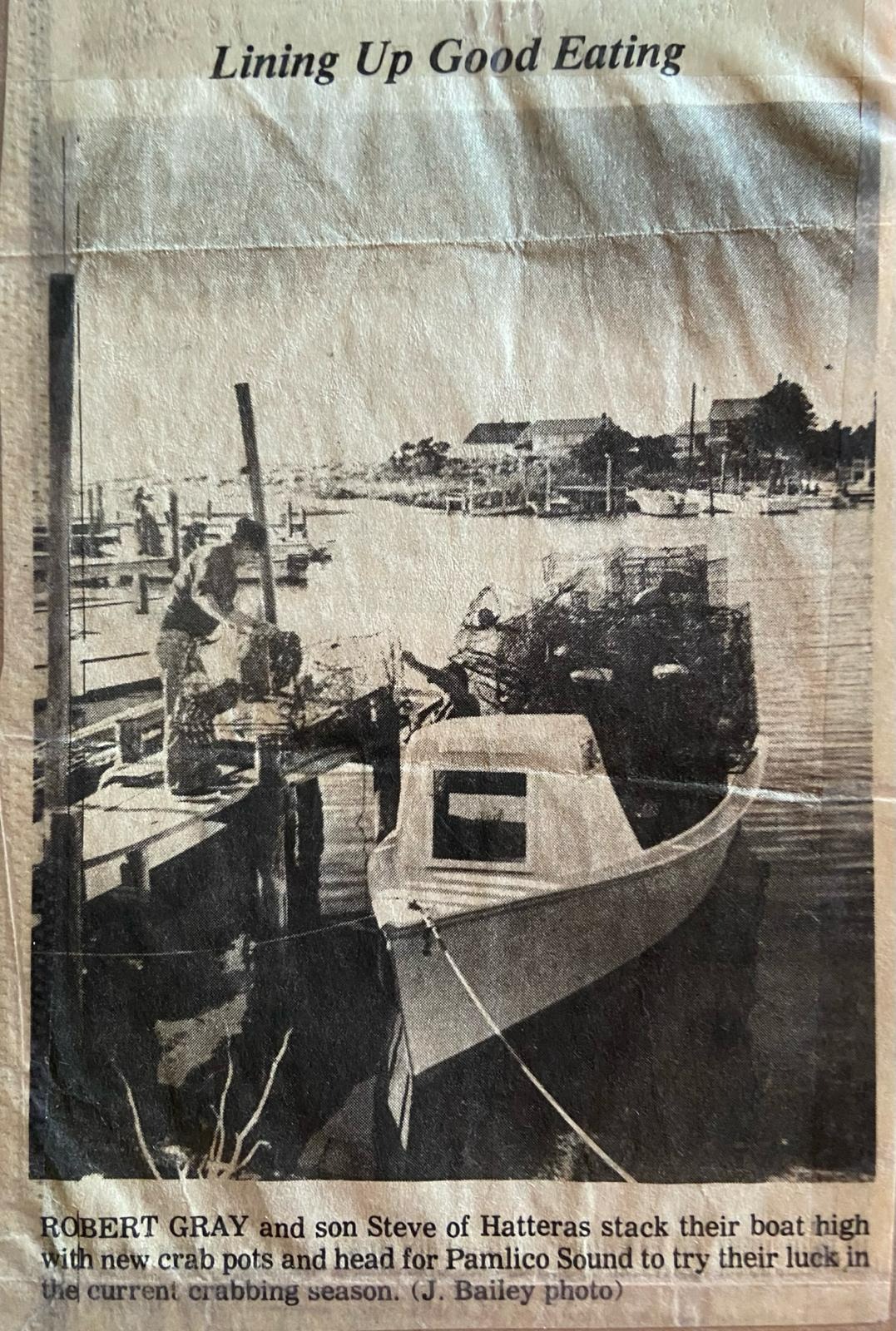

The North Carolina coast, ranging from the isolated barrier islands in Dare County to the busy port city of Wilmington, seems a beautiful paradise to any outsider. Fishermen cast their lines into the Pamlico Sound on Hatteras Island.

On the beach adjacent, surfers paddle out through white water and float on their boards. Boats make their way through the intercoastal waterway in Wilmington, passing marshes of high green grass and blue herons nesting near the tree line.

Across the Atlantic, groups of people enter bustling restaurants in Liverpool’s Albert Docks. In Brighton, families set up their towels and coolers for a day at the pebbled beaches. Screams of joy are heard as children go down the Helter Skelter and other rides on the pier nearby.

These two regions could not be further apart, but they share the same issues. Both are scarred by generations of drug dependency. Both are facing barriers for addicts to enter treatment. And both are highly complex, misunderstood regions with a complicated history.

Former addicts, therapists, and workers at treatment centres in both countries all agree: the phenomenon of these seemingly serene coastal cities becoming centres for drug abuse is expected to persist without early intervention, accessible treatment, and government funding.

Post a comment